Migrant Fast Lane

Photographs commissioned by Bloomberg

Journalist Mike Mcdonald

Text: Mike Mcdonald

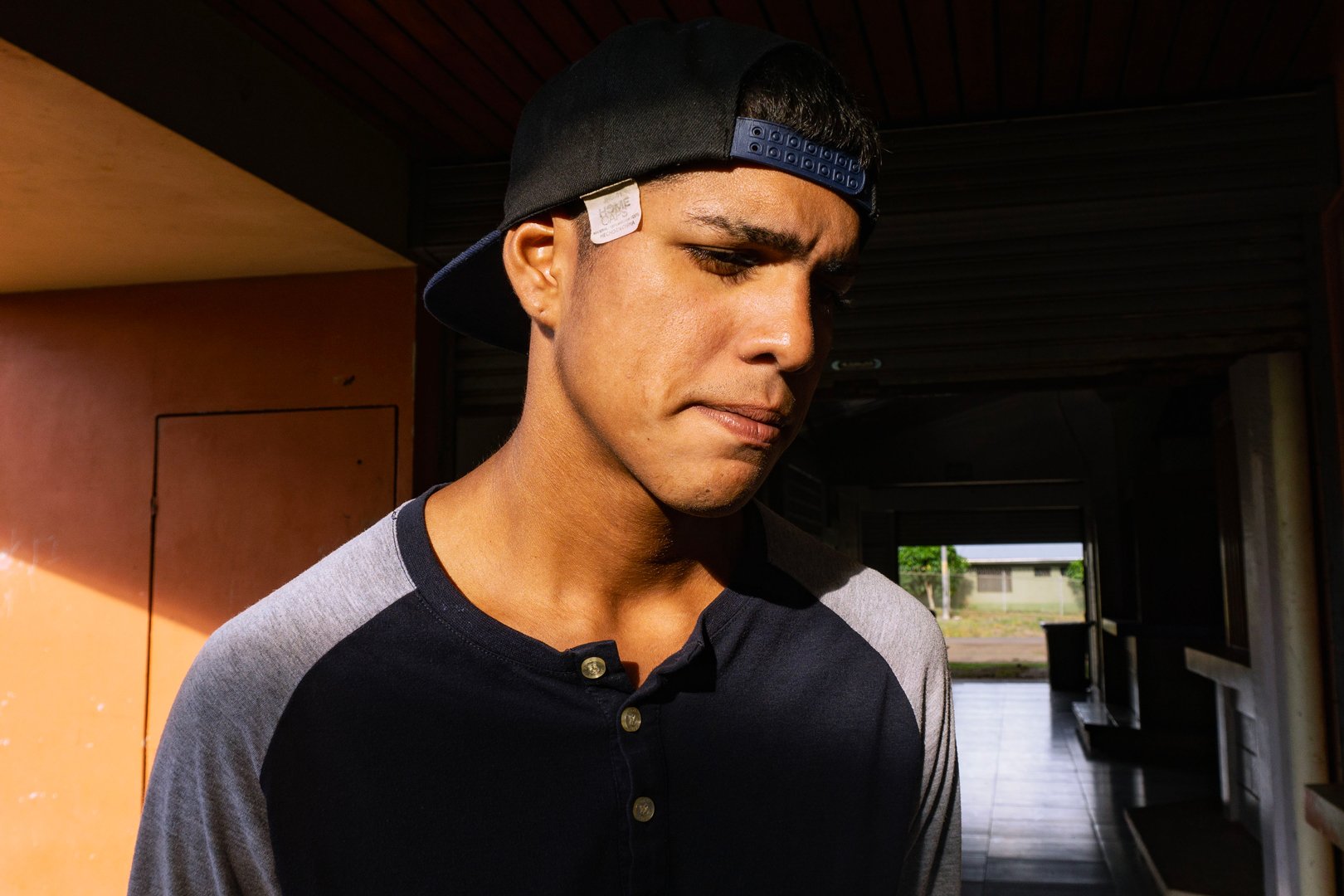

After crossing a dense jungle, torrential rains, and a raging river, Junior Mendoza boarded a bus for what would be the easiest part of a grueling journey for his family—and for the hundreds of thousands of migrants heading to the United States every day.

Between the thickets of the Darién Gap—located on the border between Panama and Colombia—and the dangerous criminal groups in Mexico, there lies a stretch of Central America where the journey north is typically made by bus, with relative comfort and safety. Those who can afford it travel 1,223 kilometers to the Nicaraguan border with the help of a series of government-run programs.

Like U.S. President-elect Donald Trump, the governments of Panama and Costa Rica do not want migrants to remain in their countries, where resources are already scarce. Once migrants have crossed the Darién, it makes more sense—and is more efficient—to ensure they reach their destination, rather than get stuck along the way. This fast-moving stage of the migrant journey presents a challenge for Trump, who needs the cooperation of other countries to achieve his goal of stopping the flow of undocumented immigration. Mendoza, a construction worker, fled Venezuela with his wife and three children to seek asylum in the U.S. and to find jobs that pay more than the $20 a week they earned back home. He had hidden $600 in his daughter’s diaper bag to protect it from thieves, but lost it while crossing a river. When his family reached Panama in November, they used what little money they had left to buy dry clothes and were quickly transported north by bus to the Nicaraguan border, arriving with their backpacks, tents, and blankets.

Trump’s hardline stance could threaten the bus program, even as the two Central American governments pressure the U.S. for more aid to handle the influx of people. His transition team has reached out to Mexico and El Salvador to host some of the millions of undocumented immigrants who will be deported under his mass deportation plan. His new border czar, meanwhile, wants to completely shut down access through the Darién. In December, the number of people taking this dangerous route fell to its lowest level in nearly three years, ahead of next week’s inauguration.

The president-elect’s transition team did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the bus program on Wednesday.

Panama began deportation flights in mid-2024, returning over 1,000 migrants with criminal records to their home countries. But that’s only a fraction of the more than 300,000 people who crossed the Darién in 2024. The U.S. helped fund the program, but Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino is seeking more support amid the worsening crisis in Venezuela.

“Mr. Trump needs to understand that his other border with the U.S. is in the Darién, and we need to start solving this bilaterally,” Mulino told the press in November. “Panama is doing what it can, investing an outrageous amount of money every year. The U.S. needs to realize this is its problem, not Panama’s.”

Trump recently took aim at Mulino, saying the U.S. could use military power to take control of the Panama Canal, a key route for global trade. Mulino, for his part, reiterated that the canal belongs to Panama and called Trump’s claims about inflated prices and Chinese interference in the waterway baseless.

“The bus was a totally different experience. We sat down, rested our feet,” Mendoza said. “The Darién is horrible.”

The agreement to transport migrants by bus to the Nicaraguan border was signed in October 2023, after a record number of people—mostly from Venezuela—crossed the Darién, overwhelming shelters and pushing government finances to the brink. President Joe Biden and his officials praised both governments for their migration cooperation, but privately expressed concern that the program might encourage more migrants to make the journey. Last year, Costa Rica streamlined the transit of over 316,000 people.

Migrants pay about $60 per person to board buses in each country, operated by local private companies. Some buses are free for those who have waited several days or don’t have enough money. According to the Costa Rican government, these “humanitarian” trips are paid for by bus companies. Nicaraguan authorities charge $150 per person for entry, according to migrants and police officers on the Costa Rican side of the border.

Cordero was traveling with his 6-year-old son and his 15-year-old pregnant daughter and didn’t have the money. He found a strong enough Wi-Fi signal to send WhatsApp messages to his sister in Dallas, who said she would send the money to a local Western Union branch a few blocks from the bus stop.

“It’s a scam,” he said. “Everyone wants 20%, even people with no official uniform who don’t work for a government or company. 20% here, 20% there. Cuba’s been in crisis for 60 years. How do they think we have all this money?”

Cubillas and his wife waited under a tree on the Costa Rican side of the border, trying to come up with a plan. A bus dropped off another group of migrants. They marched along a dirt path that skirted a brick wall near the official checkpoint. One of them raised a peace sign with his hand, and the group disappeared into Nicaragua.

“It happens every day,” said Bernie Vargas, a Costa Rican migration official. “They go around the fence through the blind spot.”

But not everyone is so lucky. Venezuelan migrant Jefferson Acuña and his wife Amelis Márquez were robbed in the Darién—losing their money and phones. They had been sleeping in tents behind the market for six days since being dropped off by the bus, selling sweets until they saved enough to pay the $150.

Cuban migrant Dariel Cubillas, a baker, said he had no cash left. Buying bus tickets and paying bribes had drained their finances. Cubillas and his wife, a nurse, watched as groups of migrants bypassed the official checkpoint through the dirt path and disappeared into Nicaragua.